Drama, baby, drama!

What exactly is the essence of American car design?

Different shapes, cut from the same cloth (image © GM/Ford Motor Company)

The general consensus regarding the essence of American car design is that size does matter in this context more than anything else. While this obviously holds true, it’s, at best, part of an explanation, rather than its summary. Even opulence isn’t quite the core characteristic of American automotive it would appear to be at first.

Undoubtedly, American cars used to be and still tend to be larger than the rest of the world’s. Over the course of automotive history, America is also likely to have produced and fitted more chrome parts than the entire rest of the global automotive industry combined. However, the essence of American car design can be found in the American automobile’s proportions.

American Premium Economy (image © Ford Motor Company)

To understand this, one needs to look no further than at the recently discontinued, tenth-generation Lincoln Continental. A large car featuring plenty of brightwork, this Continental was the most coherently American Lincoln sedan in some time. But convincing it was not, on a fundamental level even - for its proportions were perfectly in keeping with an oversized European or South Korean mid-size saloon, rather than viscerally suggestive of American stylistic bravado. A first-generation Chrysler 300C or, employing a different idiom, a Lincoln Navigator embody American design exceptionalism far more convincingly - to say nothing of the Lincoln show cars overseen by Gerry McGovern, two decades ago. The ’17 Continental’s proportions were simply too reasonable for its own good.

The future of American luxury, then (image © Ford Motor Company)

There is no truly American car that has not some strangeness (at least from a foreign perspective) to its proportions. The 2017 Continental accordingly never stood a chance, despite all that chrome and its creators’ best intentions. Proportions extreme in one way or another form the backbone of the true American automobile, historically speaking. This also applies to the ’17 Continental’s most celebrated ancestor, Elwoood Engel’s glorious ’61 vintage Continental. That car’s sheer sides were, in fact, far more modernist and minimalistic than the European norm. The contemporary Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud was similarly large, yet its baroque decorum and more traditional proportions were rendered deeply old-fashioned by the Lincoln’s progressive forms. At its best, American car design achieved the feat of making very large cars that were impressive, rather than merely imposing - perhaps the biggest difference between today’s Navigators and Escalades, compared with Engel’s ’61 Continental.

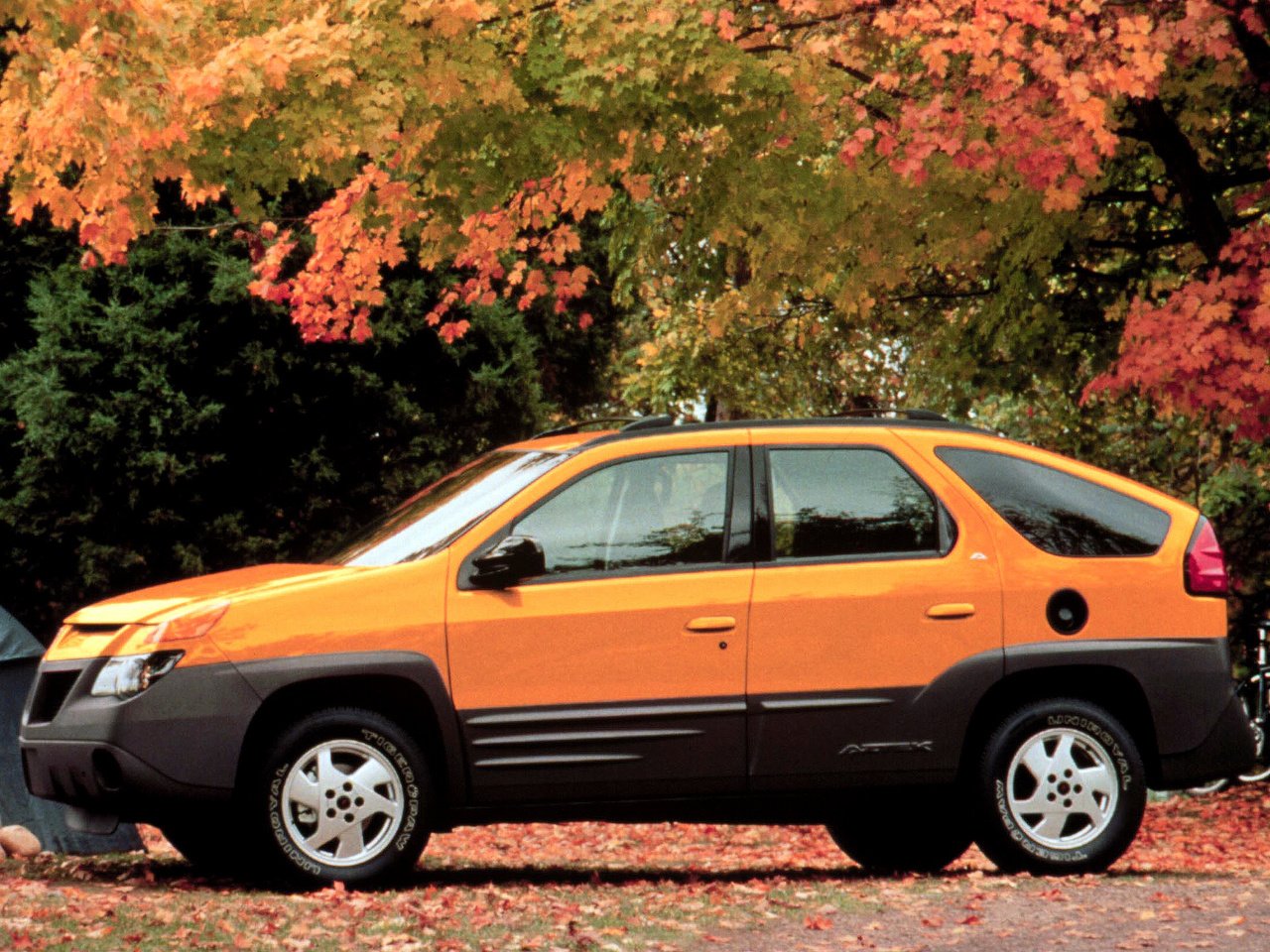

The importance of proportions is hardly limited to full-size sedans and SUVs, however. Cars as diverse as the Corvette C3, AMC Pacer, Ford Flex, Pontiac Aztek, Fisker Karma or any traditional body-on-frame sedan betray the American car’s reliance on exceptional proportions - a tradition continued today by the likes of the Tesla Model X and, inevitably, aforementioned full-size SUVs and pick-ups.

The present of American luxury (image © GM)

In American culture, bravado is what la bella figura is to Italians: larger-than-life posturing matters, as shallow and occasionally ridiculous as it may appear to foreigners. Hence US presidents decidedly not in possession of a pilot’s licence wearing leather bomber jackets when visiting air force bases. Hence the existence of something as gloriously pointless as the Theme Building at LAX airport, a basically functionless, architectural can-do statement: When you got it, why on Earth not flaunt it?

When the gesture that lends meaning (image © shutterstock)

Historically, this subliminal, yet hardly subtle context was firmly grasped by the founding fathers of US and conversely global car design. Harley Earl, the man from Hollywood, understood that rather than a mere device, the (American) car was a ‘dream machine’ first and foremost. Bill Mitchell, the man in the red suit and white trilby, then supplemented this ‘dream machine’ with ‘sheer desire’, realising that the car could act as prothesis for everything man wants to be, but isn’t.

Some of those forefathers’ successors, from Tom Gale to J Mays, from time to time put some fuel back into that ‘dream machine’. But it hasn’t been running all that smoothly for some time. Proportions don’t lie.